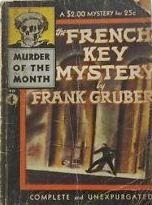

Until Saturday evening, I knew little about the Thirty Years' War beyond

the picturesque name of an incident that precipitated it (above).

But the war, it turns out, was about much more than three Catholic Habsburg envoys thrown from a window by angry Bohemian Protestants, surviving unhurt only because a dung pile cushioned their fall.

In the first hundred or so pages of

C.V. Wedgwood's

Thirty Years War (that punctuation in the title is per Wedgwood, or at least per the NYRB Classics edition of the book. In addition to pitting Habsburg and Bourbon, Catholic and Protestant, Lutheran and Calvinist, and France and Spain, a little-known dispute that survives to this day pits supporters of the possessive apostrophe in the war's name against those who prefer to go without), I have learned much about why Germany was such a mess and about how Lutheranism forged ahead. Wedgwood was a brilliant writer and historian of the good, old-fashioned kind, and for this post I'll highlight some of the larger points she makes.

The first is her acknowledgement in an introduction written eighteen years after the book first appeared that "History reflects the period in which it was written as much as any other branch of literature." In her case, that period was the 1930s, marked by economic depression and rising international tensions.

Look at that passage for a moment. How many historians today would think of what they do, of the product of their research, as

literature? Wasn't history better off, or at least a hell of a lot more readable, before it became a social science? Then consider Wedgwood's remarks that her own

"knowledge, sometimes intimate, sometimes more distant, of conditions in depressed and derelict areas, of the sufferings of the unwanted and uprooted—the two million unemployed at home, the Jewish and liberal fugitives from Germany. Preoccupation with contemporary distress made the plight of the hungry and homeless, the discouraged and the desolate in the Thirty Years War exceptionally vivid to me."

Sounds a bit like

A People's History of Central and Western Europe, doesn't it? But then you get to something like this, from the first chapter:

"The faulty transmission of news excluded public opinion from any dominant part in politics. ... The great majority of the people remained powerless, ignorant, and indifferent. The public acts and private character of individual statesmen thus assumed disproportionate significance, and dynastic ambitions governed the diplomatic relations of Europe."

I suspect that these days casual thinkers about history will regard political history and social history as opposites, the "Great Men" theory and "people's" history as irreconcilable. Not Wedgwood.

But here's the most remarkable thing about

The Thirty Years War: Wedgwood was not yet thirty years old when she wrote the book. Now, I'll see you later. I have some reading to do.

© Peter Rozovsky 2014Labels: Bohemia, C.V. Wedgwood, Defenestration of Prague, Germany, Habsburg Empire, NYRB Classics, Spain, Thirty Years War